Fostering Effective Relationships

As an educator, I understand that teaching and learning is a collaboration between all stakeholders, including students, colleagues, parents, and the community. Thus, I make it a goal to provide meaningful opportunities for parents/guardians, as partners in education, to support student learning. In my practicums, I have demonstrated this by actively communicating student needs during parent-teacher conferencing, which included sending activities home for practice when requested. This quality was mentioned by Nadia Delanoy in my December 2024 Field Instructor Narrative Assessment for Field II, “Stephanie has a natural creativity to her when it comes to designing engaging lessons. For example, she created laminated squares for students to practice their skip counting and other math practices which she was able to share with some parents to help their students during parent-teacher interviews. This was taken up very well by the parents and her partner teacher”.

I also fulfilled this indicator by sending home letters detailing the work students were doing in class to facilitate home conversations about student learning. Connecting learning to experiences outside of school is key to deepening understanding of curricular concepts.

Engaging in Career Long Learning

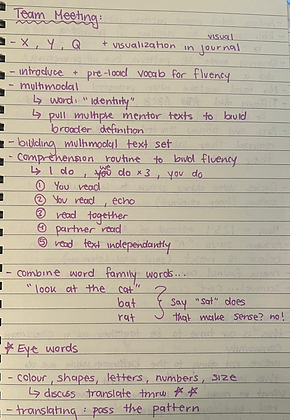

Working with colleagues is an excellent way to advance teaching practices in a way that benefits my own classroom and the broader school community. By collaborating with other teachers to build personal and collective professional capacities and expertise, I am able to gain new perspectives on challenges. In Field III, I participated in various collaborative meetings that both supported me as a pre-service teacher and allowed me to contribute to problem solving in student learning, behaviours, and other needs. These included meetings with the grade one team, as well as across grades and divisions. Collaboration with a diverse group of teachers offered unique approaches to design thinking, as well as a heightened understanding of where students are coming from and where they are heading. My partner teacher, Janelle Schiffner commented on my engagement with this indicator in my December 2024 Partner Teacher Narrative Assessment. “[Stephanie] actively engaged in Professional Learning Communities (PLC) and Collaborative Response models (CRM) to further gain feedback and strategies from other teaching professionals. She willingly collaborated with others to build her personal and collective professional capacity. This was evident when Stephanie participated in weekly Grade 1 team meetings to design meaningful and intentional tasks that are accessible to all students”. A segment of my notes from one of the grade 1 team meetings is on the right. This particular meeting introduced me to additional teaching and assessment strategies that were working well for other teachers working through the same unit as my class. I implemented these insights into my subsequent lessons.

In keeping with Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs, in order for students to be successful in learning, they must feel safe and comfortable in the classroom. Thus, it is my main goal as an educator to build the capacity to support student success in inclusive, welcoming, caring, respectful and safe learning environment. This is the foundation on which I base my classroom management. It all starts with creating a caring classroom community. Janelle Schiffner also commented on this writing, “[Stephanie] strived to treat each student fairly and provided them with a sense of belonging. This was evident as she would greet each student every morning, took time to do a daily check-in, and would remember their personal interests. Stephanie’s calm, caring and kind demeanor allowed for students to feel safe and supported in their learning.”

Demonstrating a Professional Body of Knowledge

To foster student understanding of the link between the activity and the intended learning outcomes, I create student-friendly rubrics using visual cues. These rubrics are displayed in the classroom and students practice using them as a self-evaluation tool. To practice using a rubric with my grade 1 students in Field III, I taught a lesson where students evaluated their math work by placing a sticker on the happy or sad face for each outcome. To encourage growth, when students realized an error, I guided them revise their work instead of selecting the sad face. This resulted in increased understanding of the expectations and learning outcomes, while also providing opportunity for formative assessment.

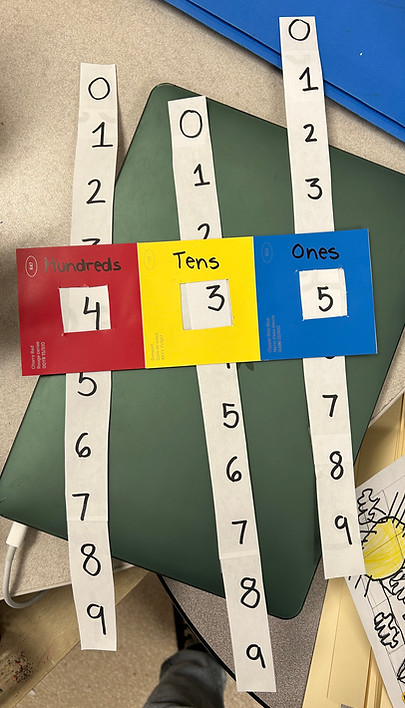

Assessment is an ongoing process that I always ensure is thread throughout my lessons, not just at the end. To accurately assess a student’s understanding of learning outcomes, I apply student assessment and evaluation practices that provide a variety of methods through which students can demonstrate their achievement of the learning outcomes. This includes offering multiple entry points, providing students with ample opportunities to showcase their skills, and using different types of assessments. For example, I have used student interviews, written evaluations, use of manipulatives, and drawings as evidence for assessment. In my April 2024 Field II Field Instructor Narrative Assessment, Nadia Delanoy commented on my use of diversification of opportunities for formative assessment. She wrote, “In one math class, Stephanie used centers and created game-based learning using dice, a number line, and other engaging methods to help students identify numbers falling in the hundreds digits. This worked very well for a diverse split class and her intentional groupings helped the student with the number sense foci”.

I often use instructional strategies to engage students in meaningful learning activities based on a knowledge of how students develop as learners by employing collaborative strategies such as the “I do, we do, you do” model. For example, for a grade 1 math lesson during my Field III, I created a routine of learning a new type of pattern each day. I began by modelling, describing, labelling, and extending a pattern on chart paper. We then tried one as a class and students actively participated in completing the rest of the chart. Students then completed a similar activity in their math journal where they had creative freedom to choose how they represented patterns.

Establishing Inclusive Learning Environments

I always account for diversity and differentiation in all my planning, from physical classroom design, classroom management, unit planning, and everything in between. I firmly believe that all students can be successful in the classroom, and it is my role to provide the right conditions in which they can thrive. Since there were many high needs in my Field III placement, I consistently used appropriate universal and targeted strategies and supports to address students' strengths, learning challenges and areas for growth. I catered my teaching practices, lesson planning, and classroom management strategies to the student’s needs, including using my Spanish language knowledge to support an English as an Additional Language (EAL) student whose first language was Spanish. An excerpt from a lesson plan I taught in this class can be seen on the right. This is a snapshot of the ways in which I planned for diversity. My partner teacher, Janelle Schiffner also commented on this in my December 2024 Partner Teacher Narrative Assessment. She wrote, “Stephanie worked with a diverse classroom which included students with English as an Additional Language (EAL), Autism, ADHD, Expressive/Receptive Speech, and Selective Mute. She has supported these students with scaffolding, modified tasks, manipulatives, work systems, visuals, sensory tools, and body breaks. Stephanie led whole group discussions and activities that promote belonging to give students a better understanding that we all have strengths and we all learn differently.”

One of my key focuses when planning for diversity is empowering students at all levels. When students feel successful, they are more engaged and willing to participate in learning tasks. Understanding individual student strengths allows me to design lessons that provide opportunities for student leadership. I found this strategy to be very effective in my Field III placement. By intentionally choosing students for tasks that match their skill set, I observed increased confidence and academic achievement, with a decrease in disruptive behaviours. My partner commented on this, writing, “[Stephanie] would provide students with leadership opportunities to empower capacity for learning. This environment encouraged engaged and active learning where all students were appreciated and supported”.

When addressing this section of the TQS, it is pertinent that I authentically know my students. This is one of the reasons relationship building with students is so important to me. My field instructor, Nadia Delanoy commented on this quality in my April 2024 Field II Instructor Narrative Assessment, writing “Stephanie knew through her relationship with the students how best to accommodate in a split class to ensure those in the higher grade were engaged and challenged and the students in the lower grade was not overwhelmed. This is not easy to do for a new preservice teacher and Stephanie did this with confidence and grace”. Thus, by understanding my students, I am equipped to recognize and respond to specific learning needs of individual or small groups of students. In Field II, I used strategies such as levelled groups and target intervention activities to support students. My partner teacher, Joan Weinman described my work in my April 2024 Partner Teacher Narrative Assessment writing, “Individual and targeted activities were created and sent home for extra practice for students that Stephanie was able to identify as needing support through her assessments. A combined classroom has extra challenges that Stephanie was able to address. The managing of different curriculum expectations, understanding a variety of learning levels and preparing activities that can be scaffolded was successfully achieved”.

Applying Foundational Knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit

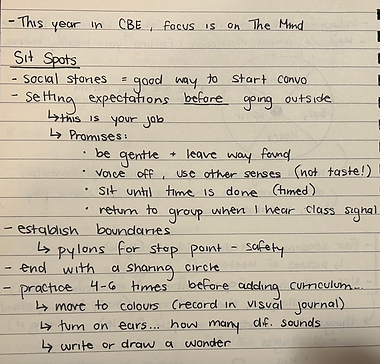

Through my participation in professional development sessions at my placement school in Field III, I became aware of the ways in which I can support student achievement by engaging in collaborative, whole school approaches to capacity building in First Nations, Métis and Inuit education. In a session regarding Sit Spots, I gained insight into the ways in which we can authentically integrate FNMI ways of knowing, being, and doing. This is a school-wide instructional strategy in my placement school for Field III. There are numerous benefits to Sit Spots, including boosting student engagement, curiosity, and reflection. Furthermore, it is an excellent way to connect students to the land, which is a professional goal of mine. After participating in this professional development session, I began to reflect on the ways in which I could apply this knowledge to my lesson planning and teaching practices. A segment of my notes from the session are on the left.

I am continuously working towards integrating FNMI into the fabric of my lesson planning. In order to provide authentic opportunities for this, I begin with using the programs of study to provide opportunities for all students to develop a knowledge and understanding of, and respect for, the perspectives and experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit. For example, in a grade 1 social studies lesson I developed, I integrated social studies outcomes regarding community with Indigenous walking pedagogy. According to this method of teaching, the act of walking provides ample opportunity to connect with the land, engage in reflective thinking practices, and learn. In this lesson, students reflected on how the land makes them feel, observed the world around us, and participated in a sharing circle. I also connected the lesson to Walking Together, a children’s book written by Indigenous author Elder Dr. Albert D. Marshall and a professor of early childhood education, Louise Zimanyi. I often use children’s literature to making connections to FNMI experiences and perspectives. My partner teacher for Field II, Joan Weinman, commented on this in my April 2024 Partner Teacher Narrative Assessment, writing “[Stephanie] took the opportunity to develop foundational knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit through literacy with the students”.

Adhering to Legal Frameworks and Policies

A critical responsibility of a teacher is ensuring the safety of students. In my Field III placement, student circumstances required my partner teacher and I to enact safety plans to ensure the wellbeing of the focus student, their peers, teachers, support staff, and the wider school community. We discussed our safety plan in collaborative team meetings and with the school’s Resource Learning Leader. I actively participated in these meetings by suggesting potential solutions and engaging in creative design thinking to address the challenge. We put various measures in place depending on student needs, including behavioural strategies, preferential seating, designated safe spaces, staggered entry, and coordinating with support staff to remove the student from the classroom if the situation escalated. Through engaging in practices consistent with policies and procedures established by the school authority, I was able to ensure the safety of my students, colleagues, and myself. In addition to fulfilling this indicator through Student Safety Plans, I also conduct my lessons to align within the parameters of school safety policy. For example, in my Community Walk Lesson for Field III, safety procedures were discussed with students prior to the lesson and successfully executed during the lesson. During the walk, we stayed within the area of the school grounds, as determined by the school authority. Furthermore, I ensured the walk was scheduled during a period we had support staff so students who needed individual attention outdoors were effectively supported.

I understand the gravity of being entrusted with a classroom of students and hold the care of my students to the highest regard. Recognizing that the professional practice of a teacher is bound by standards of conduct expected of a caring, knowledgeable and reasonable adult entrusted with the care of students extends to all areas of teaching. I keep this principal in mind when designing lessons, engaging with students, and interacting with parents and colleagues. It is imperative that I maintain the confidentiality of students, act professionally, and keep a calm atmosphere of respect and understanding in the classroom. My partner teacher from Field III, Janelle Schiffner, commented on this quality in my December 2024 Partner Teacher Narrative Assessment writing, “[Stephanie] is familiar with the expectations and policies in place while responsible for the care and education of students. [She] ensures confidentiality with all legal documents maintains the responsibility that students must feel safe at school”.

Connecting to the TQS

Fostering Effective Relationships is one of the most important aspects of my role as a teacher and brings me great joy in my practice. It is a skill that is often commented on in my evaluations and as I reflect on the ways in which I implement the Teaching Quality Standard, I have realized that it is the thread that connects how I implement each of the stems. In his book chapter, “Teaching as indwelling between two curriculum worlds”, Aoki (2004) highlights that for teachers to effectively carry out the curriculum-as-plan (i.e., as outlined in the Programs of Study and the TQS), teachers must understand the intricacies of their students. He calls these intricacies the curriculum-as-lived-experience. It is our job as teachers to link these two types of curricula, which I do through authentic relationships. Having such relationships are relevant to all areas of the TQS. For example, it is through these that I am more aware of the implications of Adhering to Legal Policies and Frameworks. These guidelines are more than just rule following. From my experiences in Field II and III, I understand the emotional stakes sensitive information has for students. A breach of trust would have negative repercussions for the student’s emotional wellbeing and willingness to engage, thus impacting their academic achievement and increasing disruptive behaviours.

Relationships are also key for Establishing Inclusive Learning Environments. To best respond to a challenge in the classroom, we must first authentically know our students and understand the root of the issue. This practice is frequently used in the design thinking approach to problem solving. From my experience as a pre-service teacher and educational assistant, I have been met with many challenges that required creative solutions. In the Designing for Learning class I took at Werklund, a key strategy was framing. This is helpful for approaching challenges in the classroom from new perspectives and aligns with the Engaging in Career-Long Learning competency in the TQS, given that continuous reflection at each stage is an important part of the design process. Furthermore, collaborating with peers and colleagues opens you up to new perspectives, resources, and feedback – all components of design thinking. This is another instance where relationship building comes in to play in the TQS. By maintaining positive and effective relationships with teacher colleagues, support staff, administration, and the wider community, I am able to use collaboration to further my knowledge and fill in gaps.

Upon reflecting on the TQS, an area that I have noticed that an area of improvement for me is in the Applying Foundational Knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit competency. Many of my peers have also identified this as a need for their own practices and in the education field as a whole. As such, we are able work collaboratively towards the common goal of addressing this need. In addition to working with peers and colleagues, I plan to address this gap by framing education through a relationality perspective, such as the one discussed by Donald (2022). In this lens, students unlearn the Westernized idea of individualism in favour of the Indigenous view of the self as part of larger web of connections. This has positive implications for engagement, community and relationship building, creating meaning, and developing skills of empathy in students.

References:

Aoki, T. T. (2004). Teaching as in-dwelling between two curriculum worlds. Curriculum in a New Key,159–165. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410611390-14

Donald, D. (2022). A curriculum for educating differently: Unlearning colonialism and renewing kinship relations. Education Canada, 62(2), 20-24. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=159152110&site=ehost-live